Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Mov Disord > Volume 14(3); 2021 > Article

-

Review Article

Management of Parkinson’s Disease in the COVID-19 Pandemic and Future Perspectives in the Era of Vaccination -

Yue Hui Lau1

, Keng Ming Lau2

, Keng Ming Lau2 , Norlinah Mohamed Ibrahim3

, Norlinah Mohamed Ibrahim3

-

Journal of Movement Disorders 2021;14(3):177-183.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14802/jmd.21034

Published online: July 29, 2021

1Department of Neurology, Hospital Kuala Lumpur, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

2Department of Internal Medicine, University Malaya Medical Centre, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

3Division of Neurology, Department of Internal Medicine, National University of Malaysia, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia

- Corresponding author: Yue Hui Lau, MBBS, MRCP Department of Neurology, Hospital Kuala Lumpur, 23 Jalan Pahang, Wilayah Persekutuan Kuala Lumpur, Kuala Lumpur 50586, Malaysia / Tel: +60165003600 / Fax: +60-3-26911186 / E-mail: andrealau38@gmail.com

Copyright © 2021 The Korean Movement Disorder Society

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

- The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) has led to a serious global health crisis. Increasing evidence suggests that elderly individuals with underlying chronic diseases, including Parkinson’s disease (PD), are particularly vulnerable to this infection. Changes in the routine care of PD patients should be implemented carefully without affecting the quality provided. The utilization of telemedicine for clinical consultation, assessment and rehabilitation has also been widely recommended. Therefore, the aim of this review is to provide recommendations in the management of PD during the pandemic as well as in the early phase of vaccination programs to highlight the potential sequelae and future perspectives of vaccination and further research in PD. Even though a year has passed since COVID- 19 emerged, most of us are still facing great challenges in providing a continuum of care to patients with chronic neurological disorders. However, we should regard this health crisis as an opportunity to change our routine approach in managing PD patients and learn more about the impact of SARS-CoV-2. Hopefully, PD patients can be vaccinated promptly, and more detailed research related to PD in COVID-19 can still be carried out.

- Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), has progressed rapidly into a pandemic, since its emergence in Wuhan, China, in December 2019 [1]. In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared COVID-19 a pandemic, a public health emergency of international concern [2].

- The coronaviruses, of which SARS-CoV-2 is a member, are enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA viruses with a nucleocapsid of helical symmetry [3]. SARS-CoV-2 has a spike protein, S1, that allows the virion to attach to the cell membrane by interacting with the host angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor and assists viral entry into the brain through the olfactory bulb, which is one plausible route for SARS-CoV-2 infection, especially given the anosmia in COVID-19 [3,4]. It is also postulated that SARS-CoV-2 infection may cause protein misfolding and aggregation [5]. Recent studies have suggested that the aggregation-prone protein, alpha-synuclein, plays a role in the innate immune response to viral infections among Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients [6,7].

- The typical clinical presentations of COVID-19 resemble those of viral pneumonia, with fever, sore throat, cough, fatigue, shortness of breath and gastrointestinal symptoms [8]. However, neurological manifestations have been increasingly reported and appear to be a combination of complications of systemic disease, the effects of direct viral infection, or the inflammation of the nervous system and vasculature, which can be parainfectious or postinfectious [4]. It is estimated that, given the 4.8 million COVID-19 cases worldwide, the prevalence of neurological complications will encompass a total of 1,805–9,671 patients with central nervous complications and 2,407–7,737 with peripheral nervous system complications [4]. Therefore, the number of COVID-19 patients with neurological sequelae will increase as the pandemic continues [4].

- As of March 12, 2021, a total of 118 million confirmed cases were documented by the WHO, causing more than 2.6 million deaths worldwide, with an overall mortality rate of 0.2%, involving at least 219 countries [2]. Older patients, especially those with medical comorbidities, were reported to have a higher risk of fatality [8]. Hence, elderly patients with chronic neurodegenerative diseases such as PD remain vulnerable to infection. Since the prevalence of PD is high among older age individuals, especially in those older than 80 years of age, an individualized approach in the management of PD patients affected by COVID-19 based on clinical and scientific evidence is crucial [9].

INTRODUCTION

- The Global Burden of Parkinson’s disease 2016 reported that 6.1 million individuals had Parkinson’s disease globally in 2016, compared with 2.5 million in 1990 [10]. The report also stated that the aging of populations contributed to much of that growth, as crude prevalence rates increased by approximately 74% from 1990 to 2016 and age-standardized prevalence rates increased by approximately 22% [10].

- PD is a chronic and progressive neurodegenerative disease that causes movement difficulties due to bradykinesia, rigidity and tremors. Patients with PD warrant special consideration during this pandemic due to increased vulnerability. Older and advanced-stage PD patients develop progressive rigidity of respiratory muscles and the thoracic cavity, in addition to a weakened abnormal posture and cough reflex, making them particularly susceptible to developing severe COVID-19 [11]. Moreover, fever and delirium are the main contributors to motor deterioration and respiratory tract infection among PD patients [12,13].

- Nonmotor symptoms such as fatigue, orthostatic hypotension, cognitive impairment, anxiety and psychosis also worsened with SARS-CoV-2 infection, along with limited access to healthcare resources, restrictions of mobility and reduced social interaction [14,15]. Up to 22.8% of patients with PD experienced a worsening of their psychiatric clinical condition during this pandemic, and depression was the most frequent nonmotor clinical feature reported [16]. Depression has been indicated as a specific risk factor for developing PD and has been shown to be the most common psychiatric symptom in patients with PD [17].

- Pneumonia was the most common cause of inpatient admissions, and the main cause of death among PD patients [18]. An Italian study reported that older PD patients (mean age of 78.3 years) with a long disease duration (mean duration of 12.7 years) were susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, with a high mortality rate of 40% [14]. Similarly, PD patients on advanced therapies, including deep brain stimulation and levodopa infusion therapy, were highly vulnerable, with a 50% mortality rate [14].

- As PD advances, motor fluctuations such as the wearing-off phenomenon, dyskinesia and gait freezing become more prominent, which affects mobility and the quality of life. The presence of gait freezing, motor fluctuations with ON and OFF phenomena and/or dyskinesia may make the long wait during entry-point screening more cumbersome for PD patients. Moreover, those requiring wheelchairs may require a caregiver to accompany them, leading to an influx of more hospital visitors.

- During the outbreak of COVID-19, neurologists face challenges with the management of COVID-19 patients and the existing tasks in providing care towards PD patients. Undoubtedly, adjustments for PD management should be implemented so that the continuum of care will not be affected. Although there is no robust evidence to suggest the causal association of SARS-CoV-2 infection with the development of Parkinson’s disease, many articles on COVID-19 and PD regarding the etiology, risks and consequences have been reported [9,15].

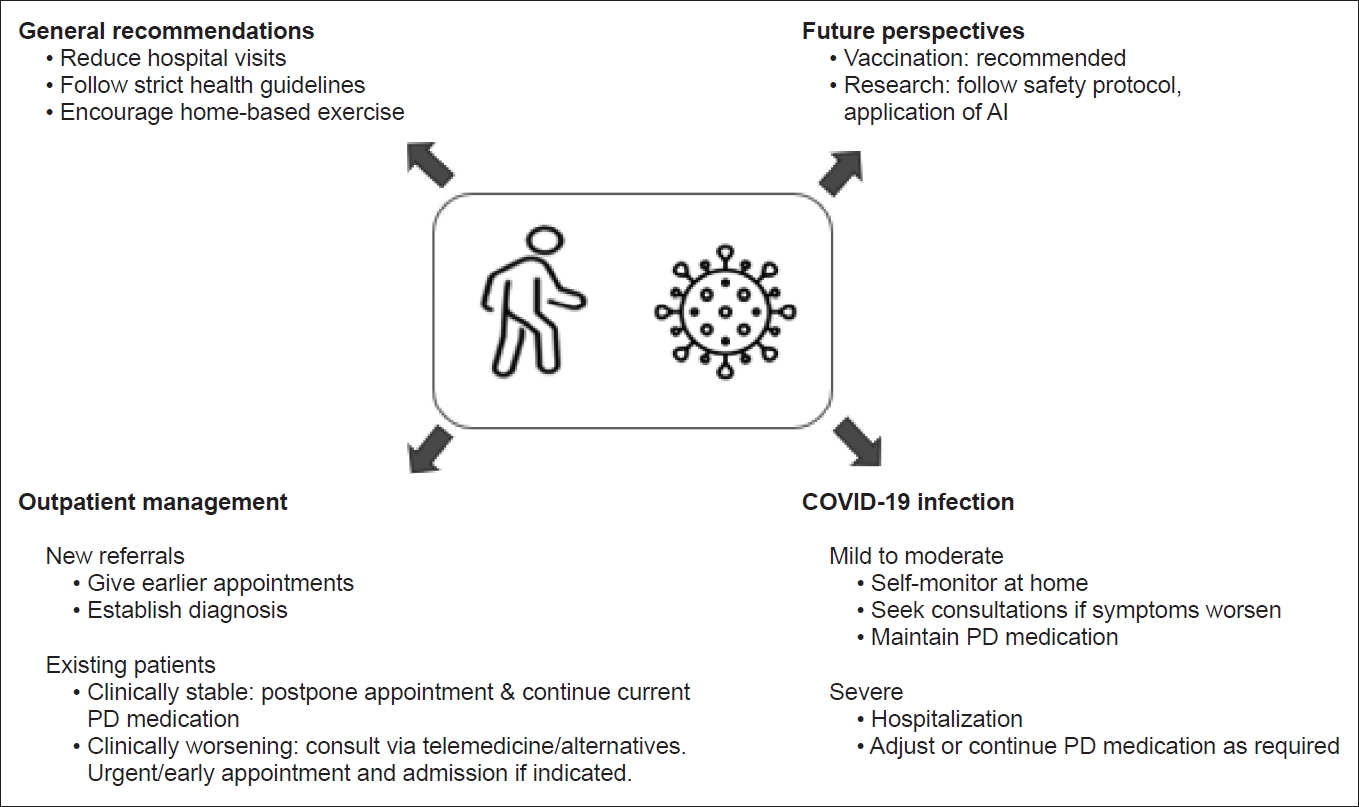

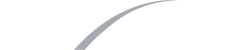

- Here, we outline practical recommendations for managing PD patients during the COVID-19 pandemic and the early phase of vaccination (Table 1, Fig. 1).

PARKINSON’S DISEASE AND COVID-19

- General recommendations

- Changes in the routine care of PD patients must be implemented carefully without affecting the quality provided. There are several published recommendations for the management of PD patients during this pandemic [19].

- PD patients should avoid unnecessary hospital visits and visits to public places. Hospital visits should be reserved for emergency reasons to reduce the risk of infection [19]. ‘‘Lockdowns” have been implemented by various governments in an attempt to curb the spread of COVID-19, and this could disrupt access to PD medication by delaying clinic appointments, interrupting delivery systems and making it difficult to access dispensaries [20,21]. Hence, adaptive strategies must be adopted to ensure an adequate supply of PD medications to the patients.

- It is also expected that there will be an influx of patients to the hospital once there is an easing of movement restrictions. It is thus suggested that a screening telephone call be conducted by trained medical personnel to determine if hospital review is required. Stable PD patients should maintain their current medication regimen unless new complications arise. New referrals to establish diagnoses should be seen as priorities, so that investigations and treatment can be initiated early. Patients should adhere to strict guidelines to prevent the risk of contracting SARS-CoV-2 infection. Patients are also encouraged to carry out daily home exercises, according to their ability to prevent inactive lifestyles that could exacerbate motor and mood symptoms [19].

- Outpatient management–the use of telemedicine and telerehabilitation

- The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends delaying elective ambulatory provider visits and the use alternatives that do not need face-to face consultation, such as telemedicine [22,23]. Telemedicine should be used for outpatient clinic visits if possible, as the validity of telemedicine in the assessment of PD patients has been shown in many studies [19,21]. Most studies also emphasized that reliable motor examinations, such as the Motor section of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS-III), should be performed via telemedicine [24]. The Movement Disorder Society–Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) is recommended, but there are limitations in assessing rigidity and postural instability [25]. A previous study suggested a modified version of the motor UPDRS without rigidity and retropulsion pull to be used in remote assessments of patients [26,27].

- The optimization of motor and nonmotor symptoms, and adjustments for medication-related side effects could be easily performed through telemedicine [19]. This could reduce the risk of COVID-19 transmission while maintaining adequate care for PD patients. In addition, physiotherapy and rehabilitation services could also be delivered online. Patients may also benefit from virtual reality exercise games or home exercise instruments, as recommended by rehabilitation experts.

- Since these facilities are still lacking in less developed countries, online videoconferencing platforms that ensure patient confidentiality should be urgently developed in line with the guidelines by local health authorities. Wearable devices and smartphone applications can be used to monitor symptoms at home, which also allows more continuous data-driven management of PD [28,29]. Alternatively, phone calls or patient-recorded videos, sent via text messaging applications or text messaging with patient videos could be used on a case-to-case basis, when teleconferencing facilities are limited.

- Online rehabilitation services should be offered. If not available, patients should be guided to online programs that have been established for PD. A study among PD patients showed that effective speech therapy could be delivered via online consultation using a smartphone [30]. These teleconsultations and telerehabilitation services could still be maintained even in the post-COVID era, and would reduce unnecessary hospital visits, especially in those with mobility issues. Patients could also continue with their guided- rehabilitation programs from the comfort and safety of their homes. Additionally, patients should also be guided to establish online resources to facilitate home exercises and rehabilitation.

- Elective deep brain stimulation surgery (DBS) and patients on DBS therapy

- With the uncertainty of the pandemic, it was suggested that deep brain stimulation surgeries should be postponed [19]. However, we propose that elective DBS for PD should be continued, albeit with tight selection criteria, with priority given to patients who are most debilitated. Postoperative follow-up for suture removal and stimulation settings should be timed appropriately to prevent multiple clinic visits.

- Stable patients already on DBS therapy may not require regular follow-up unless they encounter acute problems. For instance, patients may unexpectedly experience the end-of-battery life of the implantable pulse generator. As abrupt withdrawal of subthalamic nucleus stimulation may lead to a life-threatening akinetic crisis similar to neuroleptic malignant syndrome, urgent battery replacement is required [23,31]. Similarly, infections related to lead implantation and lead fractures will require immediate intervention [25,32].

- Recognizing and managing PD patients with COVID-19

- In cases of mild to moderate COVID-19, patients have been advised to manage their symptoms at home and for hospitalization if clinically indicated, particularly if respiratory symptoms significantly worsen [9,33]. It is recommended that all previous PD medications should be continued to prevent rigidity and respiratory distress [19]. For PD patients who wish to self-medicate with over-the-counter (OTC) products, it is imperative to consult a neurologist or pharmacists, as some OTC products can interfere with their Parkinson’s symptoms and medications [33].

- Antihistamines such as diphenhydramine and dimenhydrinate have anticholinergic properties that can worsen constipation, confusion and urinary symptoms. Anticholinergic side effects can be further enhanced, such as dry mouth, blurred vision, and urinary retention, if PD medications, such as benztropine or trihexyphenidyl, are taken together with antihistamines [33]. Caution should be taken to prevent the possibility of drug interaction with monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI), which could lead to severe sympathomimetic crisis, particularly cough syrups containing dextromethorphan or nasal decongestants containing pseudoephedrine, phenylephrine or phenylpropanolamine, as MAOIs can enhance the serotonergic effects of dextromethorphan, which can lead to serotonin syndrome [33,34].

- Amantadine, which is commonly used in PD, has been repurposed to treat COVID-19, as it plays a potential role as an antiviral agent against SARS-CoV-2 by blocking the matrix-2 (M2) protein ion channel and disrupting lysosomal gene expression to reduce viral replication [22,33,35]. Antivirals, such as favipiravir, atazanavir, and lopinavir/ritonavir, and antimalarial agents, such as chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine, are being tested for COVID-19, and thus far, no specific interactions with dopaminergic medications have been reported [23].

- A high index of suspicion is necessary, especially if patients present with acute deterioration in their motor symptoms. A recent article highlighted two cases of advanced PD patients with severe COVID-19 who presented initially with acute and unexplained worsening of motor symptoms a few days prior to the onset of fever. Both cases deteriorated rapidly, with eventual death, highlighting that PD patients are prone to severe COVID-19 [14]. The overlapping of nonmotor symptoms of PD, such as anosmia and fatigue, with COVID-19 symptoms may somewhat contribute to a delay in the diagnosis of COVID-19.

- With regard to the care strategy for PD patients admitted to the ICU, effort should be made to ensure that PD patients continue to receive anti-PD therapy [31]. Abrupt cessation of PD medications should be avoided to prevent deterioration in parkinsonism and dopamine agonist withdrawal syndrome [31]. Highly fractionated doses of levodopa solution via a nasogastric tube, at 2-hour to 3-hourly intervals could be given to PD patients with severe infection, akinesia and dysphagia [31]. For patients who are on apomorphine pump therapy and levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG), continuous infusion may be continued. There is no evidence that LCIG therapy would be less beneficial than oral treatment, even though patients have other underlying severe illnesses. The initiation of an apomorphine pump in the ICU is generally not advised, however, it can be considered only if malignant akinesia occurs [31]. If apomorphine vials are not available or if the situation does not permit the establishment of an extra infusion system, oral levodopa should be given. Intravenous amantadine is much less efficacious and carries risks, including QTc prolongation and agitation [31]. For psychosis and delirium related to infection, sequential withdrawal of anticholinergics, monoamine oxidase B inhibitors and catechol-O-methyltransferase inhibitors (COMT-Is) is recommended.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF PD IN THE COVID ERA

- Sequelae of parkinsonism in COVID-19

- Postviral parkinsonism, which has been described historically as encephalitis lethargica, can occur either immediately or much later following an acute episode of viral illness [9,35-37]. Clinical presentations typically involve upper limb bradykinesia and stiffness associated with frequent episodes of kinesia paradoxica, oculogyric crisis, and psychiatric symptoms. Encephalitis lethargica could be just a contributing factor rather than a prerequisite to developing postencephalitic parkinsonism [37]. According to recent estimates of the incidence of PD and documented global burden of SARS-CoV-2 infection, it is expected that approximately 10,000 newly-diagnosed cases of PD among those infected above the age of 40 will occur [2,38,39].

- While it is possible that the COVID-19 pandemic could lead to a rise in the incidence of parkinsonism globally, the role of the virus in causing or exacerbating Parkinson’s disease appears unlikely at this time [9]. However, the aggravation of specific motor and nonmotor symptoms secondary to the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic has been reported [9].

- The best way to identify populations that are likely to develop parkinsonism will be to create a health registry of COVID-19 patients who undergo regular long-term neurological follow-up for the signs of prodromal PD/parkinsonism, as well as blood tests for neurofilament light chain for signs of neurodegeneration [40].

- Vaccination

- A total of 289 experimental COVID-19 vaccines are in development as of February 3, 2021. Sixty-six of which were in different phases of clinical testing, including 20 in phase III currently [41]. To date, 5 out of these 66 vaccines, which were developed by BioNTech in collaboration with Pfizer; AstraZeneca in partnership with Oxford University; and Gamaleya, Moderna, and Sinopharm, working together with the Beijing Institute, have been authorised by the WHO [41]. The approved COVID-19 vaccines have been proven to be effective in preventing the severe and mild forms of the disease. It is evident that high efficacy (> 90%) has been proven regardless of race, sex, age, and or comorbidities [42-45]. To date, a total of 300 million vaccine doses have been administered worldwide [2].

- The International Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorder Society (MDS) has released a COVID-19 vaccine statement to address aspects of COVID-19 vaccination among PD patients [42]. PD patients are encouraged to receive COVID-19 vaccination unless there is a specific contraindication for the vaccination. The MDS also recommended vaccination because the benefits and risks are similar to those in the general (age-matched) population so that PD patients can be protected against the disease and its complications. Moreover, the administration of COVID-19 vaccination is not expected to interfere with current PD medications and is not known to interact with the neurodegenerative process in PD [42]. Many countries have initiated the vaccination programs for their citizens, and clearly, the priority has been given to the elderly age group, especially those with comorbidities, including Parkinson’s disease.

- It has been reported that even though vaccines seem safe for older adults, it is important to remain cautious when administering the vaccine to very frail and terminally ill elderly persons with PD [42]. Vaccinated persons with PD have to strictly adhere to the national health guidelines to reduce exposure to and the transmission of COVID-19 [40].

- Research

- The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on PD research and educational activities. It is important to justify conducting any clinical and preclinical studies on PD in the midst of the pandemic [46]. Priority should be aimed at clinical studies without direct contact with patients and studies that can be conducted in nonclinical fields [46]. The prioritization of preventive, diagnostic and interventional measures is also of paramount importance [47]. Principles in maintaining trial integrity during the COVID-19 pandemic have been proposed [48].

- Stringent efforts should be adopted to comply with new safety protocols regarding physical distancing, protective personal equipment, and the reduction of site visits as well as minimizing the number of researchers physically present at times [46]. International collaboration among all countries is particularly essential in addressing public health crises, including the management of PD [47]. The application of artificial intelligence with an integrated-omics approach can better define disease models and discover new therapeutic targets in the field of PD [49,50]. Finally, a coordinated effort and dedicated databases of PD cohorts with and without COVID-19 should be available for future studies [38].

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

- Embracing the new norm with a practical and careful approach towards the care of PD is of utmost importance to ensure that patients are not unnecessarily exposed to SARS-CoV-2 and that the management of PD is optimized. The utilization of telemedicine for clinical consultation and assessment could lead to a paradigm shift in the care of PD patients. Future research related to PD is crucial in the long pandemic, and outreach programs for vaccination in the PD patient population should be initiated promptly.

CONCLUSION

-

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Yue Hui Lau, Norlinah Mohamed Ibrahim. Data curation: all authors. Formal analysis: all authors. Investigation: all authors. Methodology: all authors. Project administration: all authors. Resources: all authors. Software: Keng Ming Lau. Supervision: Norlinah Mohamed Ibrahim. Validation: all authors. Visualization: Yue Hui Lau, Keng Ming Lau. Writing—original draft: Yue Hui Lau, Norlinah Mohamed Ibrahim. Writing—review & editing: Yue Hui Lau, Keng Ming Lau.

Notes

- The authors thank the Ministry of Health Malaysia for administrative assistance.

Acknowledgments

| Use of telemedicine | |

| Optimization of motor and non-motor symptoms [19] | |

| Adjustments for medication-related side effects [19] | |

| Reliable to assess Motor section of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS-III) [25] | |

| Speech therapy, physiotherapy and rehabilitation services [30] | |

| Alternatives: Wearable devices and smartphone applications, or Phone calls or patient-recorded videos, sent via text messaging | |

| Deep brain stimulation surgery (DBS)/therapy | |

| Selective DBS for PD patients with urgent indication | |

| Post-operative follow-up for suture removal and stimulation settings should be timed appropriately | |

| Urgent intervention for end of battery life of the implantable pulse generator, leads fracture and infection related to lead implantation [23,25,31,32] | |

| Medications | |

| Caution of drug interaction with PD medication [33] | |

| Avoid abrupt cessation of PD medications [31] | |

| Highly fractionated doses of levodopa solution can be given via a nasogastric tube [31] | |

| Apomorphine pump therapy and levodopa/carbidopa intestinal gel (LCIG) continuous infusion can be continued [31] | |

| Intravenous amantadine is less efficacious [31] | |

| Sequential withdrawal of anticholinergics, MAO-B inhibitors and COMT-I is recommended for psychosis and delirium related to infection | |

| Sequelae of Parkinsonism in COVID-19 | |

| The need of proper registry for prevalence/incidence | |

| The use of biomarker (e.g., neurofilament light chain for signs of neurodegeneration [40]) | |

| Vaccination | |

| Recommended in PD patients [42] | |

| Do not interfere with the current PD medication [42] | |

| Not known to interact with the neurodegenerative process in PD [42] | |

| Research | |

| Non-clinical or clinical studies without direct contact with patients should be prioritized [46] | |

| Encourage studies related to preventive, diagnostic and interventional measures [47] | |

| Enhance the international collaboration in PD research [47] | |

| Application of artificial Intelligence with an integrated-omics approach [49,50] | |

- 1. Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med 2020;382:1199–1207.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. World Health Organization (WHO). WHO coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; c2021 [accessed on 2021 Jan 25]. Available at: https://covid19.who.int.

- 3. Zumla A, Chan JF, Azhar EI, Hui DS, Yuen KY. Coronaviruses - drug discovery and therapeutic options. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2016;15:327–347.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Ellul MA, Benjamin L, Singh B, Lant S, Michael BD, Easton A, et al. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol 2020;19:767–783.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Gordon DE, Jang GM, Bouhaddou M, Xu J, Obernier K, White KM, et al. A SARS-CoV-2 protein interaction map reveals targets for drug repurposing. Nature 2020;583:459–468.PubMedPMC

- 6. Ezzat K, Pernemalm M, Pålsson S, Roberts TC, Järver P, Dondalska A, et al. The viral protein corona directs viral pathogenesis and amyloid aggregation. Nat Commun 2019;10:2331.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Tulisiak CT, Mercado G, Peelaerts W, Brundin L, Brundin P. Can infections trigger alpha-synucleinopathies? Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci 2019;168:299–322.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Onder G, Rezza G, Brusaferro S. Case-fatality rate and characteristics of patients dying in relation to COVID-19 in Italy. JAMA 2020;323:1775–1776.ArticlePubMed

- 9. Sulzer D, Antonini A, Leta V, Nordvig A, Smeyne RJ, Goldman JE, et al. COVID-19 and possible links with Parkinson’s disease and parkinsonism: from bench to bedside. NPJ Parkinsons Dis 2020;6:18.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 10. GBD 2016 Parkinson’s Disease Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of Parkinson’s disease, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol 2018;17:939–953.PubMedPMC

- 11. van Wamelen DJ, Leta V, Johnson J, Ocampo CL, Podlewska AM, Rukavina K, et al. Drooling in Parkinson’s disease: prevalence and progression from the non-motor international longitudinal study. Dysphagia 2020;35:955–961.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 12. Umemura A, Oeda T, Tomita S, Hayashi R, Kohsaka M, Park K, et al. Delirium and high fever are associated with subacute motor deterioration in Parkinson disease: a nested case-control study. PLoS One 2014;9:e94944. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 13. Zheng KS, Dorfman BJ, Christos PJ, Khadem NR, Henchcliffe C, Piboolnurak P, et al. Clinical characteristics of exacerbations in Parkinson disease. Neurologist 2012;18:120–124.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 14. Antonini A, Leta V, Teo J, Chaudhuri KR. Outcome of Parkinson’s disease patients affected by COVID-19. Mov Disord 2020;35:905–908.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 15. Merello M, Bhatia KP, Obeso JA. SARS-CoV-2 and the risk of Parkinson’s disease: facts and fantasy. Lancet Neurol 2021;20:94–95.ArticlePubMed

- 16. Janiri D, Petracca M, Moccia L, Tricoli L, Piano C, Bove F, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and psychiatric symptoms: the impact on Parkinson’s disease in the elderly. Front Psychiatry 2020;11:581144.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 17. Burn DJ. Beyond the iron mask: towards better recognition and treatment of depression associated with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2002;17:445–454.ArticlePubMed

- 18. Okunoye O, Kojima G, Marston L, Walters K, Schrag A. Factors associated with hospitalisation among people with Parkinson’s disease - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2020;71:66–72.ArticlePubMed

- 19. Papa SM, Brundin P, Fung VSC, Kang UJ, Burn DJ, Colosimo C, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on Parkinson’s disease and movement disorders. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2020;7:357–360.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 20. Brown EG, Chahine LM, Goldman SM, Korell M, Mann E, Kinel DR, et al. The effect of the COVID- 19 pandemic on people with Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2020;10:1365–1377.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 21. Crawford A, Serhal E. Digital health equity and COVID-19: the innovation curve cannot reinforce the social gradient of health. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e19361. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 22. Bhidayasiri R, Virameteekul S, Kim JM, Pal PK, Chung SJ. COVID-19: an early review of its global impact and considerations for Parkinson’s disease patient care. J Mov Disord 2020;13:105–114.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 23. Rajan R, Krishnan S, Kesavapisharady KK, Kishore A. Malignant subthalamic nucleus-deep brain stimulation withdrawal syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2016;3:288–291.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 24. Cubo E, Trejo Gabriel-Galán JM, Seco Martínez J, Alcubilla CR, Yang C, Arconada OF, et al. Comparison of office-based versus home web-based clinical assessments for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2012;27:308–311.ArticlePubMed

- 25. Goetz CG, Stebbins GT, Luo S. Movement Disorder Society-Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale use in the Covid-19 era. Mov Disord 2020;35:911.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 26. Abdolahi A, Scoglio N, Killoran A, Dorsey ER, Biglan KM. Potential reliability and validity of a modified version of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale that could be administered remotely. Parkinsonsim Relat Disord 2013;19:218–221.Article

- 27. Schoffer KL, Patterson V, Read SJ, Henderson RD, Pandian JD, O’Sullivan JD. Guidelines for filming digital camera video clips for the assessment of gait and movement disorders by teleneurology. J Telemed Telecare 2005;11:368–371.ArticlePubMed

- 28. Espay AJ, Hausdorff JM, Sánchez-Ferro Á, Klucken J, Merola A, Bonato P, et al. A roadmap for implementation of patient-centered digital outcome measures in Parkinson’s disease obtained using mobile health technologies. Mov Disord 2019;34:657–663.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 29. Motolese F, Magliozzi A, Puttini F, Rossi M, Capone F, Karlinski K, et al. Parkinson’s disease remote patient monitoring during the COVID-19 lockdown. Front Neurol 2020;11:567413.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 30. Chan MY, Chu SY, Ahmad K, Ibrahim NM. Voice therapy for Parkinson’s disease via smartphone videoconference in Malaysia: a preliminary study. J Telemed Telecare 2021;27:174–182.ArticlePubMed

- 31. Fasano A, Antonini A, Katzenschlager R, Krack P, Odin P, Evans AH, et al. Management of advanced therapies in Parkinson’s disease patients in times of humanitarian crisis: the COVID-19 experience. Mov Disord Clin Pract 2020;7:361–372.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 32. Jitkritsadakul O, Bhidayasiri R, Kalia SK, Hodaie M, Lozano AM, Fasano A. Systematic review of hardware-related complications of deep brain stimulation: do new indications pose an increased risk? Brain Stimul 2017;10:967–976.ArticlePubMed

- 33. Elbeddini A, To A, Tayefehchamani Y, Wen C. Potential impact and challenges associated with Parkinson’s disease patient care amidst the COVID-19 global pandemic. J Clin Mov Disord 2020;7:7.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 34. Pray WS. Interactions between nonprescription products and psychotropic medications. US Pharm 2007;32:12–15.

- 35. Anwar F, Naqvi S, Al-Abbasi FA, Neelofar N, Kumar V, Sahoo A, et al. Targeting COVID-19 in Parkinson’s patients: drugs repurposed. Curr Med Chem 2021;28:2392–2408.ArticlePubMed

- 36. Monteiro L, Souza-Machado A, Valderramas S, Melo A. The effect of levodopa on pulmonary function in Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Ther 2012;34:1049–1055.ArticlePubMed

- 37. Hoffman LA, Vilensky JA. Encephalitis lethargica: 100 years after the epidemic. Brain 2017;140:2246–2251.ArticlePubMed

- 38. Fearon C, Fasano A. Parkinson’s disease and the COVID-19 pandemic. J Parkinsons Dis 2021;11:431–444.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 39. Hirsch L, Jette N, Frolkis A, Steeves T, Pringsheim T. The incidence of Parkinson’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology 2016;46:292–300.ArticlePubMed

- 40. Beauchamp LC, Finkelstein DI, Bush AI, Evans AH, Barnham KJ. Parkinsonism as a third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic? J Parkinsons Dis 2020;10:1343–1353.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 41. Wouters OJ, Shadlen KC, Salcher-Konrad M, Pollard AJ, Larson HJ, Teerawattananon Y, et al. Challenges in ensuring global access to COVID-19 vaccines: production, affordability, allocation, and deployment. Lancet 2021;397:1023–1034.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 42. Bloem BR, Trenkwalder C, Sanchez-Ferro A, Kalia LV, Alcalay R, Chiang HL, et al. COVID-19 vaccination for persons with Parkinson’s disease: light at the end of the tunnel? J Parkinsons Dis 2021;11:3–8.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 43. Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 vaccine. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2603–2615.ArticlePubMed

- 44. Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, Jackson LA, Roberts PC, Makhene M, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med 2020;383:2427–2438.ArticlePubMed

- 45. Ramasamy MN, Minassian AM, Ewer KJ, Flaxman AL, Folegatti PM, Owens DR, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine administered in a prime-boost regimen in young and old adults (COV002): a single-blind, randomised, controlled, phase 2/3 trial. Lancet 2021;396:1979–1993.PubMed

- 46. Tan EK, Albanese A, Chaudhuri K, Lim SY, Oey NE, Shan Chan CH, et al. Adapting to post-COVID19 research in Parkinson’s disease: lessons from a multinational experience. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2021;82:146–149.ArticlePubMed

- 47. AlNaamani K, AlSinani S, Barkun AN. Medical research during the COVID-19 pandemic. World J Clin Cases 2020;8:3156–3163.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 48. Fleming TR, Labriola D, Wittes J. Conducting clinical research during the COVID-19 pandemic: protecting scientific integrity. JAMA 2020;324:33–34.ArticlePubMed

- 49. Welton T, Tan EK. Applying artificial intelligence to multi-omic data: new functional variants in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2021;36:347.ArticlePubMed

- 50. Adly AS, Adly AS, Adly MS. Approaches based on artificial intelligence and the internet of intelligent things to prevent the spread of COVID-19: scoping review. J Med Internet Res 2020;22:e19104. ArticlePubMedPMC

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Increasing exercise with a mobile app in people with Parkinson’s disease: a pilot study

Jong Hyeon Ahn, Dongrul Shin, Dongyeong Lee, Hye Young Kim, Jinyoung Youn, Jin Whan Cho, Suzanne Kuys

Brain Impairment.2024;[Epub] CrossRef - Potential convergence of olfactory dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease and COVID-19: The role of neuroinflammation

Hui Li, Junliang Qian, Youcui Wang, Juan Wang, Xiaoqing Mi, Le Qu, Ning Song, Junxia Xie

Ageing Research Reviews.2024; 97: 102288. CrossRef - A large survey on COVID-19 vaccination in patients with Parkinson’s disease and healthy population

Chao Han, Zhen Zhen Zhao, Piu Chan, Fang Li, Chun Ling Chi, Xin Zhang, Yan Zhao, Jing Chen, Jing Hong Ma

Vaccine.2023; 41(43): 6483. CrossRef - Role of SARS-CoV-2 in Modifying Neurodegenerative Processes in Parkinson’s Disease: A Narrative Review

Jeremy M. Morowitz, Kaylyn B. Pogson, Daniel A. Roque, Frank C. Church

Brain Sciences.2022; 12(5): 536. CrossRef - Deep Learning Paradigm for Cardiovascular Disease/Stroke Risk Stratification in Parkinson’s Disease Affected by COVID-19: A Narrative Review

Jasjit S. Suri, Mahesh A. Maindarkar, Sudip Paul, Puneet Ahluwalia, Mrinalini Bhagawati, Luca Saba, Gavino Faa, Sanjay Saxena, Inder M. Singh, Paramjit S. Chadha, Monika Turk, Amer Johri, Narendra N. Khanna, Klaudija Viskovic, Sofia Mavrogeni, John R. Lai

Diagnostics.2022; 12(7): 1543. CrossRef - Movement disorders in COVID-19 times: impact on care in movement disorders and Parkinson disease

Sabrina Poonja, K. Ray Chaudhuri, Janis M. Miyasaki

Current Opinion in Neurology.2022; 35(4): 494. CrossRef - Viruses, parkinsonism and Parkinson’s disease: the past, present and future

Valentina Leta, Daniele Urso, Lucia Batzu, Yue Hui Lau, Donna Mathew, Iro Boura, Vanessa Raeder, Cristian Falup-Pecurariu, Daniel van Wamelen, K. Ray Chaudhuri

Journal of Neural Transmission.2022; 129(9): 1119. CrossRef

Comments on this article

KMDS

KMDS

E-submission

E-submission

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite