Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Mov Disord > Volume 17(1); 2024 > Article

-

Brief communication

A Survey of Perspectives on Telemedicine for Patients With Parkinson’s Disease -

Jae Young Joo1,2

, Ji Young Yun3

, Ji Young Yun3 , Young Eun Kim4

, Young Eun Kim4 , Yu Jin Jung5

, Yu Jin Jung5 , Ryul Kim6

, Ryul Kim6 , Hui-Jun Yang7

, Hui-Jun Yang7 , Woong-Woo Lee8

, Woong-Woo Lee8 , Aryun Kim9

, Aryun Kim9 , Han-Joon Kim2

, Han-Joon Kim2

-

Journal of Movement Disorders 2024;17(1):89-93.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14802/jmd.23130

Published online: August 22, 2023

1Department of Neurology, Uijeongbu Eulji Medical Center, Eulji University, Uijeongbu, Korea

2Department of Neurology, Movement Disorder Center, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

3Department of Neurology, Ewha Womans University Seoul Hospital, Ewha Womans University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea

4Department of Neurology, Hallym University Sacred Heart Hospital, Hallym University College of Medicine, Anyang, Korea

5Department of Neurology, Daejeon St. Mary’s Hospital, College of Medicine, The Catholic University of Korea, Daejeon, Korea

6Department of Neurology, Inha University Hospital, Inha University College of Medicine, Incheon, Korea

7Department of Neurology, Ulsan University Hospital, University of Ulsan College of Medicine, Ulsan, Korea

8Department of Neurology, Nowon Eulji Medical Center, Eulji University, Seoul, Korea

9Department of Neurology, Chungbuk National University Hospital, Chungbuk National University College of Medicine, Cheongju, Korea

- Corresponding author: Han-Joon Kim, MD, PhD Department of Neurology, Movement Disorder Center, Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul National University College of Medicine, 101 Daehak-ro, Jongno-gu, Seoul 03080, Korea / Tel: +82-2-2072-2278 / Fax: +82-2-3672-7553 / E-mail: movement@snu.ac.kr

Copyright © 2024 The Korean Movement Disorder Society

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

- 1,290 Views

- 123 Download

ABSTRACT

-

Objective

- Parkinson’s disease (PD) patients often find it difficult to visit hospitals because of motor symptoms, distance to the hospital, or the absence of caregivers. Telemedicine is one way to solve this problem.

-

Methods

- We surveyed 554 PD patients from eight university hospitals in Korea. The questionnaire consisted of the clinical characteristics of the participants, possible teleconferencing methods, and preferences for telemedicine.

-

Results

- A total of 385 patients (70%) expressed interest in receiving telemedicine. Among them, 174 preferred telemedicine whereas 211 preferred in-person visits. The longer the duration of disease, and the longer the time required to visit the hospital, the more patients were interested in receiving telemedicine.

-

Conclusion

- This is the first study on PD patients’ preferences regarding telemedicine in Korea. Although the majority of patients with PD have a positive view of telemedicine, their interest in receiving telemedicine depends on their different circumstances.

- With advancements in mobile and electronic technologies, interest in telemedicine has gradually increased, and telemedicine has already been implemented in several countries, including the USA, countries in the European Union, and Japan [1,2]. As public understanding and clinical experiences have increased since the COVID-19 pandemic, telemedicine has become an emerging model of the future.

- Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder, and the progression of motor symptoms impairs mobility. Therefore, compared to other chronic diseases, patients with PD have more difficulty visiting hospitals and often require the help of caregivers. For this reason, PD is a suitable disease for telemedicine, and studies have shown that PD patients and their guardians are satisfied with telemedicine [3,4]. However, there have been no previous studies on the perspectives of patients with PD regarding telemedicine in Korea. This study aimed to investigate the perspectives regarding telemedicine among patients with PD in Korea.

INTRODUCTION

- We surveyed PD patients from eight university hospitals in Korea from October 2022 to February 2023 (Supplementary Table 1 in the online-only Data Supplement). PD patients who visited the outpatient clinic were asked to complete a questionnaire on their perspectives regarding telemedicine. The questionnaire (Supplementary Materials 1 and 2 in the online-only Data Supplement) consisted of 13 questions regarding sex, age, place of residence, disease duration, symptom severity, possible teleconferencing methods, preference between telemedicine and in-person visits, interest in paying for telemedicine, and interest in receiving telemedicine treatment for specific symptoms. All questions were composed of multiple-choice items. Basically, this study was exploratory and descriptive statistics were obtained. When appropriate, the data were compared using the chi-square test, and the linear-by-linear association test was used to assess differences in telemedicine preference and disease severity, disease duration, or travel time to the hospital.

MATERIALS & METHODS

- In total, 554 patients (268 females) completed the questionnaire. The respondents ranged in age from their 30s to 80s, with 37.5% in their 70s and 31.4% in their 60s. Disease duration ranged from 1 to 3 years (26.8%), 3 to 5 years (20.2%), and 5 to 10 years (22.2%), respectively. Hoehn and Yahr Scale (H&Y) stage 1 was the most common (52.8%), followed by H&Y stage 2 (22.3%) and H&Y stages 4 and 5 (12.1%). Regarding the time required to visit the hospital, 64.4% answered that it took them less than one hour, 22.4% answered 1 to 2 hours, 7.4% answered 2 to 3 hours, 1.6% answered 3 to 4 hours, and 4.2% reported more than 4 hours (Table 1, Supplementary Figure 1 in the online-only Data Supplement).

- A total of 146 patients (26.4%) always required assistance from caregivers when visiting the hospital whereas 305 patients (55.1%) could visit the hospital alone. Although 72.7% (403 patients) had Wi-Fi at home (Table 1), 33.2% were unable to use a video conference system without the help of caregivers, and 17.7% were unable to use the system even with help.

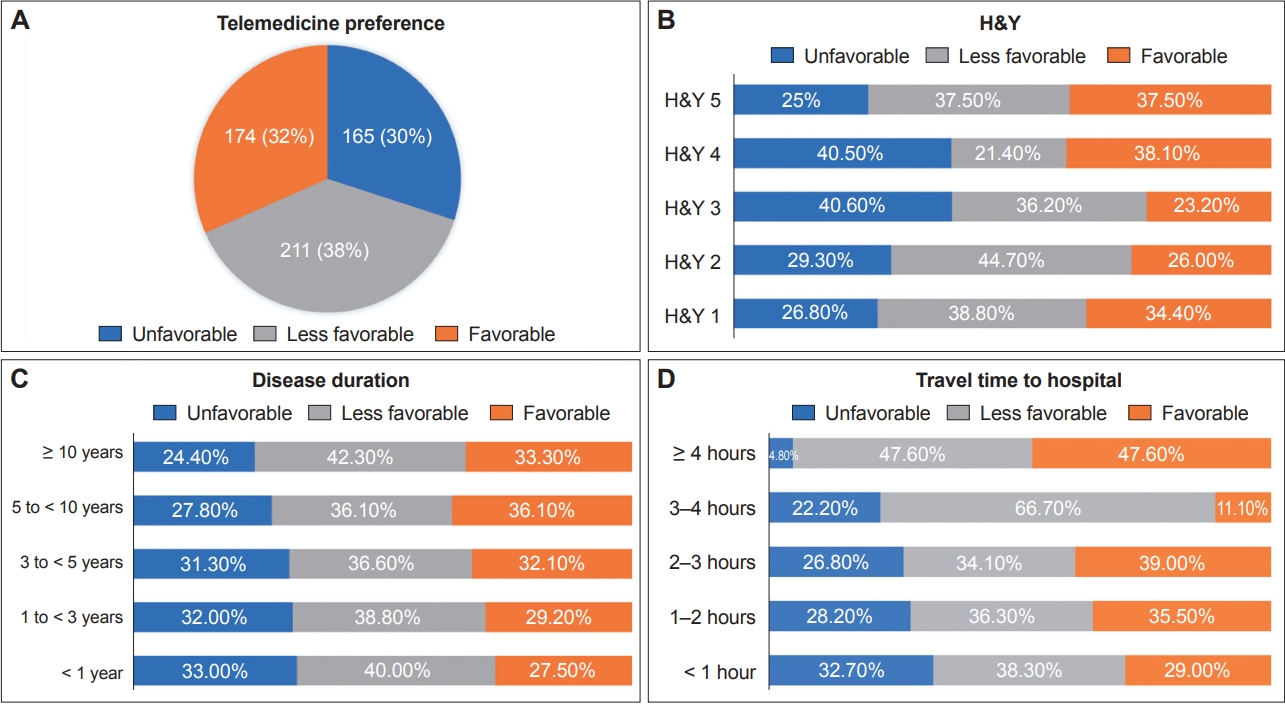

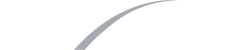

- In total 385 patients (70%) had interest in receiving telemedicine. Among them, 174 preferred telemedicine, whereas 211 preferred in-person visits (Figure 1A). Most patients answered that they wanted to receive telemedicine only from their treating physician (78.4%). Of the patients who did not intend to use telemedicine (211 patients), 50% (105 patients) answered that they were not familiar with using the devices, 23.8% (50 patients) had no internet access at home, and 22.4% (47 patients) worried that the quality of care with telemedicine would be low. A total of 3.8% (8 patients) were concerned about the leakage of personal information. Regarding the cost, 273 patients (49.2%) responded that telemedicine should be cheaper than face-to-face treatment, and 259 patients (46.7%) responded that the same level of cost as face-to-face treatment was appropriate.

- Apparently, those patients in H&Y 3 and 4 had a lower preference for telemedicine than those in H&Y stages 1 and 2. The chi-square showed that the patients with H&Y stage 3 were more likely to reply ‘unfavorable’ than the patients with H&Y stage 1 (p = 0.024) (Figure 1B). Approximately 40.5% of H&Y stage 3 or 4 patients did not want to receive telemedicine. The longer the disease duration was, the higher the percentage of patients who have intention to receive telemedicine, but there was no statistically significant difference (Figure 1C). In addition, the linear-by-linear association test showed that the longer the time required to visit the hospital, the more patients had interest in receiving telemedicine between the unfavorable group and other groups (p = 0.007) (Figure 1D). Of the patients who took less than 1 hour to visit the hospital, 67.3% wanted to receive telemedicine while 95.2% of the patients who took more than 4 hours had interest in receiving telemedicine. A total of 30.4% (44 patients) of patients who needed caregiver assistance preferred telemedicine, and 32.6% (47 patients) did not prefer telemedicine. Among patients who could visit the hospital alone, 34% (104 patients) preferred telemedicine and 28% (86 patients) did not prefer telemedicine.

- For each specific nonpharmacologic treatments, 53.3%, 49.4%, 42.7%, 49.2% and 51% had intention to receive exercise therapy, speech therapy, swallowing therapy, cognitive therapy and psychotherapy by telemedicine, respectively.

RESULTS

- Our results showed that approximately 70% of the respondents were willing to receive telemedicine. In a previous study from the USA, 76% of patients with PD showed high interest in telemedicine, which was similar to the results of our study [5]. The factors related to telemedicine preference among patients with PD were access to specialists, convenience, cost reduction, or distance from hospitals [4,5].

- In our survey, a longer time required to visit the hospital was associated with a greater interest in receiving telemedicine. A total of 67.3% of patients who took < 1 h to reach the hospital had intention to receive telemedicine, while 95.2% of patients who took more than 4 h had an interest in receiving telemedicine. This showed that distance and travel time to the hospital were important factors that affected preferences for telemedicine.

- Contrary to our expectations, only 60% of H&Y 3 and 4 patients has intention to receive telemedicine whereas more than 70% of patients at H&Y 1 and 2 has interest in receiving telemedicine. This may be because patients in the advanced stage were more likely to have motor complications and a great burden of non-motor symptoms, which make them need thorough evaluation and face-to-face discussion with the treating physician. Anyway, more than 50% of patient has intention to receive telemedicine across all H&Y stages.

- Our results showed that 81.5% of patients in their 50s has intention to receive telemedicine, whereas only 63% of patients in their 70s and 80s has intention to receive telemedicine. This suggests that younger patients with greater accessibility to video conversations and digital literacy favored telemedicine over older patients. We expect that the development of mobile technology will facilitate access to telemedicine even for elderly patients. In our survey, 72.7% (403) of patients had Wi-Fi at home, and 82% of patients were able to access the videoconferencing system with or without caregiver help. Although only 63% of those in their 70s and 80s has intention to receive for telemedicine, more than 80% of patients could use video conferencing systems with the help of their guardians, so accessibility to telemedicine is expected to increase in the future. Preferences for virtual visits [6] or telemedicine using smartphones [7-9] have been studied only recently and various videoconferencing software programs are being studied such as Facebook Messenger, FaceTime, Google Duo, Line, Skype, WeChat, Zoom or Teams [10]. In our survey, patients most preferred smartphone video calls as a videoconferencing method, followed by FaceTalk of the KakaoTalk service, and Zoom.

- Several studies have assessed telemedicine among PD patients [11]. One randomized controlled trial (RCT) of telemedicine for PD showed significant improvements in the quality of life and motor performance of patients. Most participants completed their telemedicine visit and experienced trends toward improvement in quality of life and patient satisfaction [12]. A randomized crossover pilot study of telemedicine delivered via iPads among patients with PD also showed that telemedicine could successfully be used by patients as a part of their care [13]. Another RCT using telemedicine for depression in PD patients showed that video-to-home cognitive-behavioral therapy may be an effective intervention for depression in PD [14]. These results suggested that telemedicine is feasible and has potential benefits in PD [8,9,12].

- There are several types of subspecialty care via telemedicine. As PD is a multidomain disorder, swallowing therapy [15], speech therapy, rehabilitation [16], cognitive therapy, and psychological therapy [17] are helpful for patients, and several researches on this has been conducted with favorable results. In our survey, approximately 50% of respondents had intention to receive treatment for speech and swallowing problems, cognitive and psychiatric problems and rehabilitation by telemedicine. PD is a neurodegenerative disease in which a patient’s motor ability gradually deteriorates, making it more and more difficult to visit a hospital. In addition, motor symptoms and multiple domains of nonmotor symptoms in PD gradually progress. Therefore, it is not feasible to manage all the symptoms of patients during a single visit. Therefore, not only telemedicine that replaces clinic visits, but also each treatment strategy, including nonpharmacological treatment, physical and exercise therapy, patient and guardian education, and remote monitoring needed for patients; this should be further developed and introduced in the future for holistic care of the patients.

- Conclusion

- This is the first study on PD patients’ preferences for telemedicine in Korea. Although the majority of patients with PD have a positive perspective regarding telemedicine, their interest in using telemedicine depends on their different circumstances. In Korea, telemedicine use is still limited, there are many obstacles, and further discussions are needed for PD patients.

DISCUSSION

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Table 1.

Supplementary Figure 1.

Supplementary Material 1.

-

Ethics Statement

The procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Boards of each participating center and all participants provided written informed consent.

-

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

-

Funding Statement

None

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Han-Joon Kim. Data curation: Han-Joon Kim, Ji Young Yun, Young Eun Kim, Yu Jin Jung, Ryul Kim, Hui-Jun Yang, Woong-Woo Lee, Aryun Kim. Formal analysis: Jae Young Joo, Han-Joon Kim. Investigation: Han-Joon Kim, Ji Young Yun, Young Eun Kim, Yu Jin Jung, Ryul Kim, Hui-Jun Yang, Woong-Woo Lee, Aryun Kim. Methodology: Jae Young Joo, Han-Joon Kim. Project administration: Han-Joon Kim. Resources: Han-Joon Kim, Ji Young Yun, Young Eun Kim, Yu Jin Jung, Ryul Kim, Hui-Jun Yang, Woong-Woo Lee, Aryun Kim. Supervision: Han-Joon Kim. Validation: Han-Joon Kim. Writing—original draft: Jae Young Joo, Han-Joon Kim. Writing—review & editing: Jae Young Joo, Han-Joon Kim.

Notes

- 1. Oh JY, Park YT, Jo EC, Kim SM. Current status and progress of telemedicine in Korea and other countries. Healthc Inform Res 2015;21:239–243.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Kichloo A, Albosta M, Dettloff K, Wani F, El-Amir Z, Singh J, et al. Telemedicine, the current COVID-19 pandemic and the future: a narrative review and perspectives moving forward in the USA. Fam Med Community Health 2020;8:e000530. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Ogawa M, Oyama G, Sekimoto S, Hatano T, Hattori N. Current status of telemedicine for Parkinson’s disease in Japan: a single-center cross-sectional questionnaire survey. J Mov Disord 2022;15:58–61.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 4. Qiang JK, Marras C. Telemedicine in Parkinson’s disease: a patient perspective at a tertiary care centre. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2015;21:525–528.ArticlePubMed

- 5. Spear KL, Auinger P, Simone R, Dorsey ER, Francis J. Patient views on telemedicine for Parkinson disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2019;9:401–404.ArticlePubMed

- 6. McGrail KM, Ahuja MA, Leaver CA. Virtual visits and patient-centered care: results of a patient survey and observational study. J Med Internet Res 2017;19:e177. ArticlePubMedPMC

- 7. Kim HS, Hwang Y, Lee JH, Oh HY, Kim YJ, Kwon HY, et al. Future prospects of health management systems using cellular phones. Telemed J E Health 2014;20:544–551.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 8. Dorsey ER, Venkataraman V, Grana MJ, Bull MT, George BP, Boyd CM, et al. Randomized controlled clinical trial of “virtual house calls” for Parkinson disease. JAMA Neurol 2013;70:565–570.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Dorsey ER, Achey MA, Beck CA, Beran DB, Biglan KM, Boyd CM, et al. National randomized controlled trial of virtual house calls for people with Parkinson’s disease: interest and barriers. Telemed J E Health 2016;22:590–598.PubMedPMC

- 10. Cubo E, Arnaiz-Rodriguez A, Arnaiz-González Á, Díez-Pastor JF, Spindler M, Cardozo A, et al. Videoconferencing software options for telemedicine: a review for movement disorder neurologists. Front Neurol 2021;12:745917.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 11. León-Salas B, González-Hernández Y, Infante-Ventura D, de Armas-Castellano A, García-García J, García-Hernández M, et al. Telemedicine for neurological diseases: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Neurol 2023;30:241–254.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 12. Dorsey ER, Deuel LM, Voss TS, Finnigan K, George BP, Eason S, et al. Increasing access to specialty care: a pilot, randomized controlled trial of telemedicine for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 2010;25:1652–1659.ArticlePubMed

- 13. Sekimoto S, Oyama G, Hatano T, Sasaki F, Nakamura R, Jo T, et al. A randomized crossover pilot study of telemedicine delivered via iPads in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsons Dis 2019;2019:9403295.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 14. Dobkin RD, Mann SL, Weintraub D, Rodriguez KM, Miller RB, St Hill L, et al. Innovating Parkinson’s care: a randomized controlled trial of telemedicine depression treatment. Mov Disord 2021;36:2549–2558.ArticlePubMedPDF

- 15. Theodoros D. Telerehabilitation for communication and swallowing disorders in Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinsons Dis 2021;11(s1):S65–S70.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 16. Truijen S, Abdullahi A, Bijsterbosch D, van Zoest E, Conijn M, Wang Y, et al. Effect of home-based virtual reality training and telerehabilitation on balance in individuals with Parkinson disease, multiple sclerosis, and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurol Sci 2022;43:2995–3006.ArticlePubMedPMCPDF

- 17. Latella D, Maresca G, Formica C, Sorbera C, Bringandì A, Di Lorenzo G, et al. The role of telemedicine in the treatment of cognitive and psychological disorders in Parkinson’s disease: an overview. Brain Sci 2023;13:499.ArticlePubMedPMC

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

Comments on this article

- Figure

- Related articles

-

- Copper Deficiency Myeloneuropathy in a Patient With Wilson’s Disease

- Absence of Alpha-Synuclein Aggregation in Patients With Parkinson’s Disease Complicated by Sigmoid Volvulus

- Caregiver Burden of Patients With Huntington’s Disease in South Korea

- Investigation of the Long-Term Effects of Amantadine Use in Parkinson’s Disease

- Current Status and Future Perspectives on Stem Cell-Based Therapies for Parkinson’s Disease

KMDS

KMDS

E-submission

E-submission

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite