Rapid-Onset Dystonia and Parkinsonism in a Patient With Gaucher Disease

Article information

Abstract

Biallelic mutations in GBA1 cause the lysosomal storage disorder Gaucher disease, and carriers of GBA1 variants have an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease (PD). It is still unknown whether GBA1 variants are also associated with other movement disorders. We present the case of a woman with type 1 Gaucher disease who developed acute dystonia and parkinsonism at 35 years of age during a recombinant enzyme infusion treatment. She developed severe dystonia in all extremities and a bilateral pill-rolling tremor that did not respond to levodopa treatment. Despite the abrupt onset of symptoms, neither Sanger nor whole genome sequencing revealed pathogenic variants in ATP1A3 associated with rapid-onset dystonia-parkinsonism (RDP). Further examination showed hyposmia and presynaptic dopaminergic deficits in [18F]-DOPA PET, which are commonly seen in PD but not in RDP. This case extends the spectrum of movement disorders reported in patients with GBA1 mutations, suggesting an intertwined phenotype.

Rapid-onset dystonia-parkinsonism (RDP) is a rare movement disorder characterized by the sudden onset of both dystonia and parkinsonian features. Familial cases of RDP were first reported in the 1990s, and subsequently, mutations in ATP1A3, encoding the α3 subunit of the Na+/K+ ATPase, were identified as a genetic cause [1]. Today, it is known that ATP1A3 variants are associated with a spectrum of clinical phenotypes. The clinical diagnostic criteria for RDP have primarily been descriptive, with an abrupt onset of dystonia and parkinsonism within 30 days, marked bulbar symptoms and a gradient of symptoms progressing rostrally to caudally strongly suggestive of a diagnosis [2]. Recently, simplified diagnostic criteria were proposed, including only the presence of dystonia, absence of symptoms at 18 months of age, and presence of an ATP1A3 variant [3]. However, despite these seemingly characteristic features, only 3 of 14 (21%) individuals in a cohort of patients with “probable” RDP carried a pathological variant in ATP1A3. Patients in the ATP1A3-negative cohort lacked bulbar symptoms and presented with tremor. No other genetic cause was found [4]. Identifying further gene variants resulting in RDP-like conditions may shed light on pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of this disorder.

The link between GBA1 mutations, which cause the rare lysosomal disorder Gaucher disease (GD) when biallelic, and an increased risk of Parkinson’s disease (PD) and dementia with Lewy bodies is now well established [5]. GBA1-associated parkinsonism occurs in homozygous and heterozygous mutation carriers, likely with similar frequency [6-8]. The phenotypic presentation usually resembles that of idiopathic PD and responds to dopaminergic therapy, but an earlier age of onset, more frequent nonmotor symptoms, and a more aggressive disease course are reported [9]. Similar to sporadic PD, neuropathological features include the degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and α-synuclein-containing Lewy bodies [10]. In addition, atypical neurological phenotypes have been described in GBA1 mutation carriers, including multiple system atrophy (MSA) [11] corticobasal syndrome (CBS) [12] and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) [13]. However, the association between GBA1 mutations and these other movement disorders is still uncertain. Here, we describe a patient with GD with an RDP-like presentation, further broadening this phenotypic spectrum.

CASE REPORT

This 45-year-old right-handed woman presented at age 6 with hepatosplenomegaly and short stature. Splenectomy and bone marrow aspiration were performed, revealing Gaucher cells. She developed extensive skeletal involvement, with spontaneous bone fractures and avascular necrosis of both hips and the left knee. Her genotype was N370S/R463H (p.N409S/R502H). In her late 20s, placenta-derived glucocerebrosidase enzyme replacement therapy became available, and treatment was initiated.

At 35 years of age, she was switched to recombinant glucocerebrosidase, which was tolerated initially, but during and immediately after her seventh infusion, she described experiencing dizziness, sudden rigidity, and the curling of her fingers and toes. Bilateral upper extremity (UE) tremor developed shortly thereafter. She was unable to ambulate and became wheelchair bound within a month. A year-long hospitalization ensued. She was evaluated by multiple neurologists and psychiatrists without a confirmed diagnosis. Her brain computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings were reported as normal, and fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)- positron emission tomography (PET) showed no specific abnormalities. Over the years, multiple pharmacological modalities were used to treat her symptoms, which were interpreted as parkinsonism and dystonia of unknown origin. Treatments included two trials of levodopa therapy as well as primidone, biperiden, doxepin, baclofen, mirtazapine, pramipexole, gabapentin, and propranolol. None of these treatments resulted in clinical improvement.

The patient was evaluated at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) 10 years after the onset of her symptoms. Her past medical history included orthopedic surgical interventions for skeletal manifestations of GD. Additionally, she had a history of panic attacks that responded to antidepressant therapy. At evaluation, her medications included pramipexole, doxepin, domperidone, and imiglucerase. She denied any tobacco, alcohol, or recreational drug use. Her mother, an obligate GBA1 carrier, had a history of PD as well as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. The patient denied difficulty swallowing but reported mild, diet-controlled constipation. She denied cognitive changes, vivid dreams, or concurrent depression.

Neurological examination demonstrated perceived intact cognition, fluent normal speech, and normal functioning of cranial nerves II-XII. Her University of Pennsylvania Smell Identification Test (UPSIT) score was 22/40. Masked facies was noted. A bilateral “pill rolling” tremor as well as an action tremor were present, affecting the right UE more than the left. Rigidity was significant in all extremities, with marked dystonia of the neck and shoulder. The range of motion in the lower extremities (LEs) was limited due to her dystonia. Movements of the upper extremities were slow, but objective evidence of bradykinesia in the presence of severe dystonia was unable to be unequivocally confirmed. Muscle stretch reflexes were brisk in the UEs and difficult to assess in the LEs due to contractures. She was unable to stand unassisted and could take only a few steps with the assistance of two individuals. At the NIH, a functional movement disorder expert evaluated the patient and did not find signs supporting a functional etiology. Formal neurocognitive functional testing could not be performed due to a language barrier.

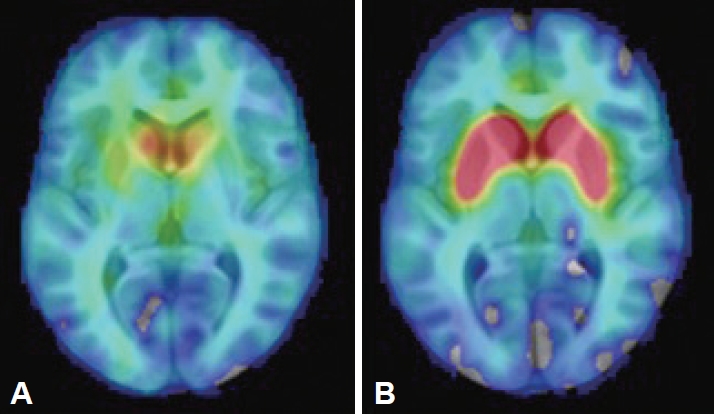

The findings of brain and abdominal MRI, cerebrospinal fluid analysis, laboratory assessments (including a ceruloplasmin test, a heavy metal screen and serum protein electrophoresis), and electroencephalogram (EEG) were interpreted as normal. Her [18F]-DOPA PET study showed bilateral dopaminergic degeneration (Figure 1). Due to the clinical presentation suggestive of RDP, ATP1A3 was analyzed by both Sanger and whole genome sequencing (WGS), but no pathogenic variants were identified. WGS revealed a pathogenic heterozygote mutation in ARSA (c.542T>G, p.Ile181Ser) when a panel of dystonia-related genes was evaluated. ARSA encodes another lysosomal enzyme, arylsulfatase A, implicated in the recessive disorder metachromatic leukodystrophy, which manifests with the regression of motor skills and spasticity. The findings of one study suggested an association between heterozygous ARSA variants and PD, but the findings were not confirmed in a larger study [14]. No other exonic variants reported as pathogenic in ClinVar were identified in known dystonia-related genes (Supplementary Material in the online-only Data Supplement).

DISCUSSION

GBA1 mutations have not previously been reported in association with an RDP-like presentation, and this case broadens the spectrum of movement disorders associated with GBA1. The sudden onset of dystonia after a potential trigger, a supporting feature in previous consensus criteria [2], suggested an ATP1A3-related disorder, but the distinct pill-rolling tremor and lack of bulbar symptoms observed in this case have mostly been described in “RDP-like” cases. While this patient had a pathogenic mutation in another lysosomal enzyme, the cause of her rare phenotype has not been proven. Furthermore, dystonia is not described in patients with type 1 GD, although it has rarely been described in patients with neuronopathic (type 3) GD [15].

This is the first RDP-like case in which presynaptic dopaminergic deficits were observed on PET imaging, a finding frequently associated with PD-like pathology. However, the patients with RDP previously imaged each carried an ATP1A3 mutation (one patient was not genotyped) [16-19]. Patients with GD without PD do not differ from controls in striatal [18F]-fluorodopa uptake [20]. Coexisting dopaminergic degeneration caused by biallelic GBA1 mutations, but clinically masked by severe RDP-like symptoms, could explain the inconsistency, but neuropathological differences between ATP1A3-related and ATP1A3-unrelated cases cannot be excluded. The lack of ATP1A3 mutations in this patient with an atypical RDP-like phenotype may shed light on the cause of the heterogeneity seen in this disorder. We cannot exclude the possibility of a modifying effect of GBA1 mutations resulting in symptoms and findings more commonly associated with PD.

Last, this case highlights the reliance on clinical judgment in the diagnosis and treatment of movement disorders. The known risk of PD for patients with GD could result in overlooking other movement disorders. Moreover, blended phenotypes can result from the combination of disease-causing variants in different genes. Here, clinical examination resulted in a second diagnosis, with potentially important counseling implications.

Supplementary Materials

The online-only Data Supplement is available with this article at https://doi.org/10.14802/jmd.23074.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary Methods

Notes

Ethics Statement

The patient was evaluated under a clinical protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board of the National Human Genome Research Institute. The patient provided signed informed consent prior to participation. The authors confirm that they have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and confirm that this work is consistent with those guidelines.

Conflicts of Interest

Dietrich Haubenberger is a full-time employee of Neurocrine Biosciences, Inc. (San Diego, CA) and receives royalties from Oxford University Press. Mark Hallett is an inventor of a patent held by National Institutes of Health (NIH) for the H-coil for magnetic stimulation for which he receives license fee payments from the NIH (from Brainsway). He is on the Medical Advisory Boards of Brainsway, QuantalX, and VoxNeuro. The other authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the Intramural Research Programs of the National Human Genome Research Institute and the National Institutes of Health.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Ellen Hertz, Grisel Lopez, Mark Hallett, Ellen Sidransky. Data curation: Ellen Hertz, Grisel Lopez, Nahid Tayebi, Ellen Sidransky. Formal analysis: Ellen Hertz, Grisel Lopez, Jens Lichtenberg. Funding acquisition: Ellen Sidransky. Methodology: Ellen Hertz, Grisel Lopez, Jens Lichtenberg, Nahid Tayebi, Ellen Sidransky. Resources: Ellen Sidransky. Supervision: Jens Lichtenberg, Nahid Tayebi, Ellen Sidransky. Writing—original draft: Ellen Hertz, Grisel Lopez, Jens Lichtenberg. Writing—review & editing: Grisel Lopez, Dietrich Haubenberger, Nahid Tayebi, Mark Hallett, Ellen Sidransky.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Daniel Eisenberg (National Institute of Mental Health) for preparing the positron emission tomography image.