Articles

- Page Path

- HOME > J Mov Disord > Volume 15(2); 2022 > Article

-

Case Report

Expanding the Clinical Spectrum of RFC1 Gene Mutations -

Dinkar Kulshreshtha

, Jacky Ganguly

, Jacky Ganguly , Mandar Jog

, Mandar Jog

-

Journal of Movement Disorders 2022;15(2):167-170.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.14802/jmd.21117

Published online: March 22, 2022

Department of Clinical Neurological Sciences, University Hospital, London, Canada

- Corresponding author: Mandar Jog, MD, FRCPC Department of Clinical Neurological Sciences, University Hospital, 339 Windermere road, London Health Sciences Centre, London, ON N6A 5A5, Canada / Tel: +1-5196633814 / Fax: +1-5196633174 / E-mail: mandar.jog@lhsc.on.ca

Copyright © 2022 The Korean Movement Disorder Society

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

ABSTRACT

- Biallelic intronic repeat expansion in the replication factor complex unit 1 (RFC1) gene has recently been described as a cause of late onset ataxia with degeneration of the cerebellum, sensory pathways and the vestibular apparatus. This condition is termed cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy, and vestibular areflexia syndrome (CANVAS). Since the identification of this novel gene mutation, the phenotypic spectrum of RFC1 mutations continues to expand and includes not only CANVAS but also slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia, ataxia with chronic cough (ACC), isolated sensory neuropathy and multisystemic diseases. We present a patient with a genetically confirmed intronic repeat expansion in the RFC1 gene with a symptom complex not described previously.

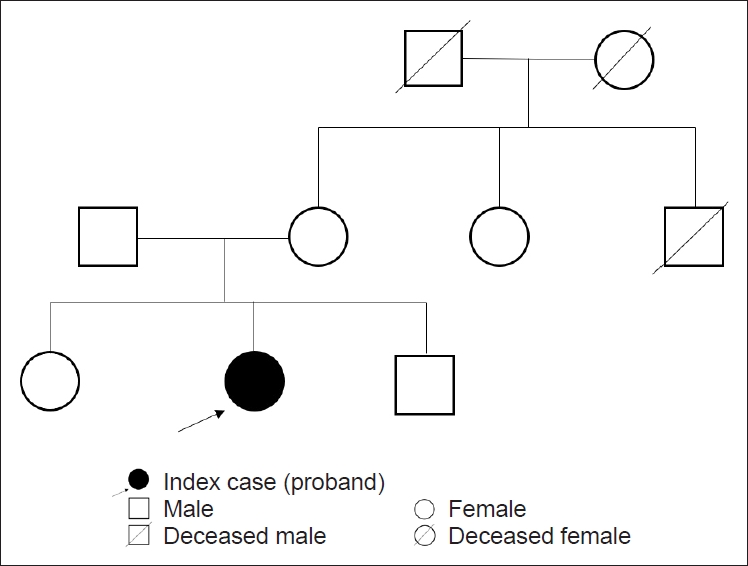

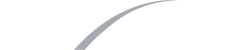

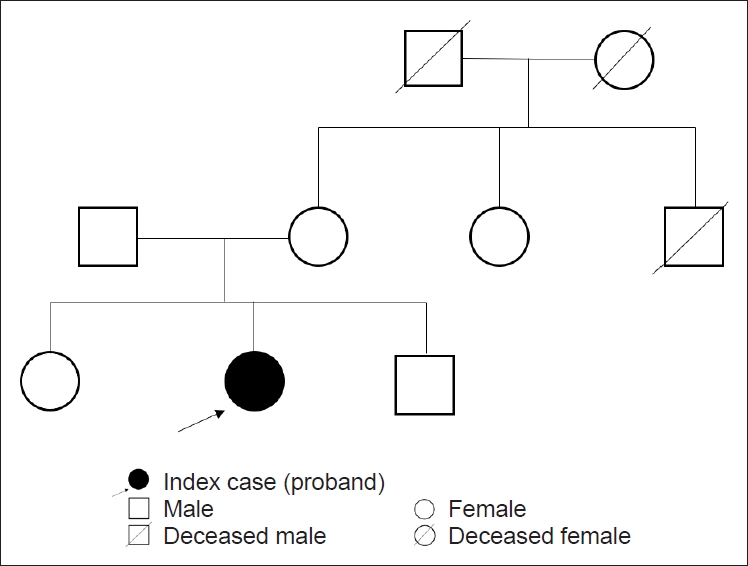

- A sixty-six-year-old female with normal perinatal and developmental history presented with progressive gait unsteadiness for the last 6 years. There was a significant past history of episodic imbalance and dizziness for many years, and the patient was diagnosed with benign paroxysmal positional vertigo, which improved on vestibular physiotherapy. No significant family history was noted (Figure 1). Her symptoms progressed with upper limb incoordination and slurring of speech for the last two years. Examination revealed a Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) score of 25/30. The eye movements were minimally affected with gaze-evoked nystagmus and mild saccadic overshoot. The head impulse test (HIT) was negative, and the VVOR was well preserved (Supplementary Video 1 in the online-only Data Supplement). Axial and appendicular cerebellar signs were present. The sensory and motor examination was normal, and reflexes were preserved (Supplementary Video 2 in the online-only Data Supplement). Bedside testing for autonomic functions was normal. Her routine blood tests and nerve conduction studies (including sensory nerve action potentials) were normal. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain showed cerebellar atrophy largely restricted to Crus 1 and 2 of the cerebellum (Figure 2). The brain stem was normal, and the ‘hot cross bun’ and the ‘putaminal rim sign’ of multiple system atrophy (MSA) were absent. The spinocerebellar ataxia (SCA) gene panel, including SCA6 (CACNA1A), the spastic paraplegia gene panel (SPG panel including SPG7), Friedreich’s ataxia gene (frataxin) testing, the autoimmune and paraneoplastic panel, and vitamin E and tissue transglutaminase (TTG) (IgA anti TTG) testing were all negative. Despite normal nerve conduction studies and VVOR being preserved, imaging characteristics suggesting CANVAS prompted us to order a repeat expansion test for the RFC1 gene. A biallelic intronic AAGGG pathogenic repeat expansion (460 repeats) was identified. Repeat sizing was performed by standard flanking PCR (F-PCR) and repeat primed PCR (RP-PCR) followed by capillary electrophoresis. The expansion differed in both size and nucleotide sequence from the reference AAAAG allele.

CASE REPORT

- CANVAS syndrome is a recent addition to the group of degenerative ataxias. In 2004, Migliaccio et al. [6] described four patients with slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia with bilateral vestibulopathy. Three of these patients had evidence of sensory neuropathy on electrophysiological testing. The genetic evaluation was negative for SCA 1, 2, 3, 6, and 7 and Friedreich’s ataxia, and the clinical and radiological presentation did not suggest MSA. Thus, the condition was termed cerebellar ataxia with bilateral vestibulopathy (CABV) [6]. Szmulewicz et al. [3] observed that all eighteen subjects with CABV had neuropathy in which the sensory nerve action potentials was not recordable. Length-dependent peripheral neuropathy dominated the clinical picture, and few patients had global sensory deficits. The complete clinical presentation of cerebellar ataxia, vestibulopathy and sensory neuropathy was termed CANVAS [3]. Cortese et al. [1] identified a biallelic AAGGG repeat expansion in the RFC1 gene in 90% of DNA samples with the CANVAS phenotype and 14% of DNA samples in other adult-onset ataxias. Their patient cohort had symptoms of cerebellar dysfunction, sensory neuropathy, oscillopsia due to impaired vestibulo-ocular reflex and mild autonomic dysfunction (postural hypotension, constipation, urogenital dysfunction and anhidrosis). A long-standing history of chronic cough preceding symptom onset by 2–3 decades was seen in 64/105 patients who tested positive for RFC1 mutations [1]. In twenty-three CANVAS patients, 93% had at least two autonomic symptoms, with electrophysiological evidence of sympathetic or parasympathetic dysfunction seen in 83% of patients [7]. Thus, CANVAS is an important differential in suspected MSA, although vestibulopathy and prominent sensory neuropathy favor a diagnosis of CANVAS. Similarly, sensory neuropathy/neuronopathy is an essential feature of the CANVAS complex. An abnormal sensory nerve conduction study was reported in all patients by Cortese et al. [1]. Postmortem studies in CANVAS cases have shown dorsal root ganglionopathy and secondary degeneration of central and peripheral sensory axons [8]. However, a substantial proportion of CANVAS patients have preserved stretch reflexes. Infante et al. [9] postulated that the relative sparing of the type 1a fibers subserving the muscle spindle afferents is responsible for the normal reflexes despite widespread neuropathy. Likewise, spasmodic cough is thought to be secondary to impaired C-fiber-mediated sensory innervation of the upper airways and esophagus, causing denervation hypersensitivity of the secondary neurons in the nucleus solitarius [9].

- Impairment of the VVOR is suggestive of vestibulopathy with cerebellar dysfunction. In isolated vestibulopathy, the smooth pursuits (SP) and optokinetic reflexes (OKR) are preserved and compensate for the abnormal vestibulo-ocular reflex (VOR). However, in cerebellar dysfunction, the VOR compensates for the abnormal SP and OKR to maintain the VVOR [6]. Impaired VVOR is clinically demonstrated by turning the head slowly while the gaze is maintained at an earth-fixed target. The compensatory eye movements in CANVAS are saccadic rather than smooth, thereby localizing the abnormality to both the cerebellar and vestibular systems [10]. Traschütz et al. [2] reported that visual compensation, sensory symptoms, and cough are strong determinants of RFC1-positive patients.

- Another radiological clue to diagnosing CANVAS, as seen in our patient, is the characteristic brain imaging findings. In fifty-six RFC1-positive patients, vermian atrophy was the most consistent finding, as it is seen in approximately 80% of patients, which is more frequent than cerebellar atrophy. Anterior and dorsal vermian involvement occur in lobules VI, VIIA and VIIB, and the hemispheric atrophy in the posterosuperior and horizontal fissures occur in Crus 1 of the cerebellum [4]. Brain stem atrophy, primarily affecting the pons and mid brain, was seen in 13% of cases and was associated with a longer disease duration and worsening eye movement abnormalities [2]. Nonspecific supratentorial abnormalities or cerebral atrophy were seen in 19% of RFC1-positive patients [5]. Our patient did not have any pontine atrophy or any cerebral atrophy disproportionate to her age.

- This patient with RFC1 biallelic expansion had pure cerebellar ataxia and a prior history of vestibular dysfunction with a normal sensory examination, both clinically and on electrophysiology. She also had a preserved VVOR with no suggestion of autonomic dysfunction or chronic cough. There was no clinical evidence suggesting CANVAS; however, the characteristic MRI finding was a strong indication for RFC1 genetic testing. Thus, in the absence of sensory involvement and preserved VVOR, which are prerequisites to CANVAS, the vermian atrophy (Crus 1) observed by MRI in patients with degenerative ataxias calls for RFC1 gene testing. This novel presentation further expands the phenotypic spectrum related to the RFC1 gene. Testing for RFC1 repeat expansion is important in patients with typical and atypical CANVAS phenotypes, including those with idiopathic sensory neuropathy, ataxia with chronic cough or idiopathic slowly progressive degenerative ataxias.

DISCUSSION

Supplementary Materials

Video 1.

Video 2.

-

Ethics Statement

Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the video recording performed for academic purposes.

-

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

-

Funding Statement

None

-

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Dinkar Kulshreshtha, Jacky Ganguly. Data curation: Dinkar Kulshreshtha, Jacky Ganguly. Supervision: Mandar Jog. Writing—original draft: Dinkar Kulshreshtha, Jacky Ganguly. Writing—review & editing: Mandar Jog.

Notes

- 1. Cortese A, Simone R, Sullivan R, Vandrovcova J, Tariq H, Yau WY, et al. Biallelic expansion of an intronic repeat in RFC1 is a common cause of late-onset ataxia. Nat Genet 2019;51:649–658.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 2. Traschütz A, Cortese A, Reich S, Dominik N, Faber J, Jacobi H, et al. Natural history, phenotypic spectrum, and discriminative features of multisystemic RFC1 disease. Neurology 2021;96:e1369–e1382.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 3. Szmulewicz DJ, Waterston JA, Halmagyi GM, Mossman S, Chancellor AM, McLean CA, et al. Sensory neuropathy as part of the cerebellar ataxia neuropathy vestibular areflexia syndrome. Neurology 2011;76:1903–1910.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 4. Dupré M, Hermann R, Froment Tilikete C. Update on cerebellar ataxia with neuropathy and bilateral vestibular areflexia syndrome (CANVAS). Cerebellum 2021;20:687–700.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 5. Cortese A, Tozza S, Yau WY, Rossi S, Beecroft SJ, Jaunmuktane Z, et al. Cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy, vestibular areflexia syndrome due to RFC1 repeat expansion. Brain 2020;143:480–490.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 6. Migliaccio AA, Halmagyi GM, McGarvie LA, Cremer PD. Cerebellar ataxia with bilateral vestibulopathy: description of a syndrome and its characteristic clinical sign. Brain 2004;127(Pt 2):280–293.ArticlePubMed

- 7. Wu TY, Taylor JM, Kilfoyle DH, Smith AD, McGuinness BJ, Simpson MP, et al. Autonomic dysfunction is a major feature of cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy, vestibular areflexia ‘CANVAS’ syndrome. Brain 2014;137:2649–2656.ArticlePubMed

- 8. Szmulewicz DJ, McLean CA, Rodriguez ML, Chancellor AM, Mossman S, Lamont D, et al. Dorsal root ganglionopathy is responsible for the sensory impairment in CANVAS. Neurology 2014;82:1410–1415.ArticlePubMedPMC

- 9. Infante J, García A, Serrano-Cárdenas KM, González-Aguado R, Gazulla J, de Lucas EM, et al. Cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy, vestibular areflexia syndrome (CANVAS) with chronic cough and preserved muscle stretch reflexes: evidence for selective sparing of afferent Ia fibres. J Neurol 2018;265:1454–1462.ArticlePubMed

- 10. Szmulewicz DJ, Waterston JA, MacDougall HG, Mossman S, Chancellor AM, McLean CA, et al. Cerebellar ataxia, neuropathy, vestibular areflexia syndrome (CANVAS): a review of the clinical features and video-oculographic diagnosis. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2011;1233:139–147.ArticlePubMed

REFERENCES

Figure & Data

References

Citations

- Serum Neurofilament Light Chain in Replication Factor Complex Subunit 1 CANVAS and Disease Spectrum

Ilaria Quartesan, Elisa Vegezzi, Riccardo Currò, Amanda Heslegrave, Chiara Pisciotta, Pablo Iruzubieta, Alessandro Salvalaggio, Gorka Fernández‐Eulate, Natalia Dominik, Bianca Rugginini, Arianna Manini, Elena Abati, Stefano Facchini, Katarina Manso, Ines

Movement Disorders.2024; 39(1): 209. CrossRef

Comments on this article

KMDS

KMDS

E-submission

E-submission

PubReader

PubReader ePub Link

ePub Link Cite

Cite